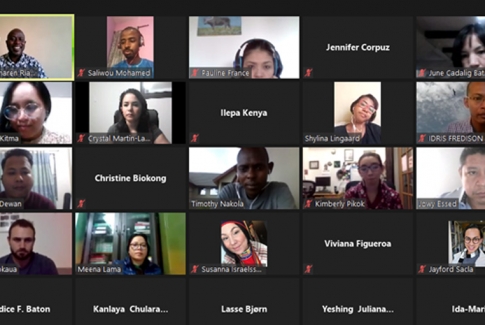

The fifth global meeting of the Indigenous Peoples’ Forum at the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) took place on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 15th day of February 2021 virtually. The meeting focused on the theme, “The Value of Indigenous Food Systems: Resilience in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The international event was attended by 540 participants from the different indigenous peoples’ organizations, communities, and institutions along with members of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples (UNFPII), representatives from IFAD and IFAD-funded projects, and several development partners.

One of the highlights of the global meeting is the Indigenous Peoples’ Week on 8 to 12 February 2021. During the Indigenous Peoples’ Week, an IPAF (Indigenous Peoples’ Assistance Facility) dedicated side event, entitled “Resilient Food Systems: Indigenous Youth Solutions in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic,” was organized on 9 February 2021 by IFAD in cooperation with the regional indigenous peoples’ organizations and implementing partners of IPAF-funded projects. The event showcased two (2) projects from the current IPAF cycle. From Asia, Pragati Koraput shared its achievements, challenges, and good practices from its IPAF-funded project, “Empowering Tribal Youth for Nutritional Food Security and Income Enhancement in Koraput District of South Odisha.” The project is being implemented in India and has contributed in enhancing the food security and nutrition of tribal communities in South Odisha. Likewise, new donors for the IPAF next cycle such as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) were introduced and participated in the said event.

The Forum included an IFAD Indigenous Peoples Awards, a newly established event which acknowledged the contribution of different development projects, implemented by IFAD, IPAF, and various indigenous peoples’ organizations, engaging indigenous peoples in rural areas. The novel initiative aimed to showcase knowledge systems and pinpoint best practices that can be replicated to scale-up better results for future and on-going projects.

Under the Best performing IPAF-funded project category, finalists were the following: African Indigenous Women Organization Central African Network (Africa), Pragati Koraput (Asia), Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo de Tarija (Latin America and the Caribbean), and Santo Sunset Environment Network (Pacific). The African Indigenous Women Organization Central African Network won the award.

The Forum culminated with the reading of the Synthesis of Deliberations which reiterated several recommendations for the United Nations Food Systems Summit, for IFAD, for governments, and indigenous peoples concerning the significance of recognizing, maintaining, and promoting indigenous knowledge, traditional practices, and food systems especially in the context of COVID-19 and its resulting impacts worldwide.

Participants called for “full, meaningful and effective participation in the planning and organization of the United Nations Food Systems Summit” while stressing the need for the “full recognition and protection of indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, territories and resources.” They also called for “the involvement and meaningful participation of indigenous peoples, including women and youth, in the design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of IFAD strategies and operations,” as they pointed out the importance of ensuring free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) before undertaking various initiatives.

As part of the resolutions of the said forum, participants committed to promote “coordination of indigenous organizations,” ensure “stronger networking and communication among indigenous peoples at all levels,” strengthen “partnerships with organizations of Afro-descendants,” and promote and facilitate “the participation, engagement and representation of indigenous youth, women and persons with disabilities.”

“Generally, the 5th Global Meeting went well though it was virtual because of the pandemic. What's good about it is the effective participation of Indigenous Peoples representatives from the various regions worldwide. IFAD committed to respond to the recommendations of indigenous peoples to ensure FPIC, disaggregation of data, and participation of indigenous peoples in IFAD operations in the country and regional levels,” observed Ruby Española, Tebtebba’s IPAF Coordinator.

Ruby Española, Tebtebba’s IPAF Coordinator

The Indigenous Peoples’ Forum, a specific initiative within the United Nations system, aims to enable indigenous peoples express their concerns, recommendations, and requests to further improve IFAD partnership and its corresponding “engagement with indigenous peoples” all over the world. The global Forum gathers every two years, with a series of regional conventions leading up to it, ensuring that the international meeting echoes the unique and diverse struggles, experiences, and recommendations of indigenous peoples from around the world.